-

Making the Brazilian ATR-72 Spin

by

[sc name=”post_comments” ][/sc]

Note: This story was corrected on August 10th at 10:23 am, thanks to the help of a sharp-eyed reader.

Making an ATR-72 Spin

I wasn’t in Brazil on Friday afternoon, but I saw the post on Twitter or X (or whatever you call it) showing a Brazil ATR-72, Voepass Airlines flight 2283, rotating in a spin as it plunged to the ground near Sao Paulo from its 17,000-foot cruising altitude. All 61 people aboard perished in the ensuing crash and fire. A timeline from FlightRadar 24 indicates that the fall only lasted about a minute, so the aircraft was clearly out of control. Industry research shows Loss of Control in Flight (LOCI) continues to be responsible for more fatalities worldwide than any other kind of aircraft accident.

The big question is why the crew lost control of this airplane. The ADS-B data from FlightRadar 24 does offer a couple of possible clues. The ATR’s speed declined during the descent rather than increased, which means the aircraft’s wing was probably stalled. The ATR’s airfoil had exceeded its critical angle of attack and lacked sufficient lift to remain airborne. Add to this the rotation observed, and the only answer is a spin.

Can a Large Airplane Spin?

The simple answer is yes. If you induce rotation to almost any aircraft while the wing is stalled, it can spin, even an aircraft as large as the ATR-72. By the way, the largest of the ATR models, the 600, weighs nearly 51,000 pounds.

Of course, investigators will ask why the ATR’s wing was stalled. It could have been related to a failed engine or ice on the wings or tailplane. (more…)

-

How the FAA Let Remote Tower Technology Slip Right Through Its Fingers

by

[sc name=”post_comments” ][/sc]

In June 2023, the FAA published a 167-page document outlining the agency’s desire to replace dozens of 40-year-old airport control towers with new environmentally friendly brick-and-mortar structures. These towers are, of course, where hundreds of air traffic controllers ply their trade … ensuring the aircraft within their local airspace are safely separated from each other during landing and takeoff.

The FAA’s report was part of President Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act enacted on November 15, 2021. That bill set aside a whopping $25 billion spread across five years to cover the cost of replacing those aging towers. The agency said it considered a number of alternatives about how to spend that $5 billion each year, rather than on brick and mortar buildings.

One alternative addressed only briefly before rejecting it was a relatively new concept called a Remote Tower, originally created by Saab in Europe in partnership with the Virginia-based VSATSLab Inc. The European technology giant has been successfully running Remote Towers in place of the traditional buildings in Europe for almost 10 years. One of Saab’s more well-known Remote Tower sites is at London City Airport. London also plans to create a virtual backup ATC facility at London Heathrow, the busiest airport in Europe.

A remote tower and its associated technology replace the traditional 60-70 foot glass domed control tower building you might see at your local airport, but it doesn’t eliminate any human air traffic controllers or their roles in keeping aircraft separated.

Max Trescott photo Inside a Remote Tower Operation

In place of a normal control tower building, the airport erects a small steel tower or even an 8-inch diameter pole perhaps 20-40 feet high, similar to a radio or cell phone tower. Dozens of high-definition cameras are attached to the new Remote Tower’s structure, each aimed at an arrival or departure path, as well as various ramps around the airport.

Using HD cameras, controllers can zoom in on any given point within the camera’s range, say an aircraft on final approach. The only way to accomplish that in a control tower today is if the controller picks up a pair of binoculars. The HD cameras also offer infrared capabilities to allow for better-than-human visuals, especially during bad weather or at night.

The next step in constructing a remote tower is locating the control room where the video feeds will terminate. Instead of the round glass room perched atop a standard control tower, imagine a semi-circular room located at ground level. Inside that room, the walls are lined with 14, 55-inch high-definition video screens hung next to each other with the wider portion of the screen running top to bottom.

After connecting the video feeds, the compression technology manages to consolidate 360 degrees of viewing area into a 220-degree spread across the video screens. That creates essentially the same view of the entire airport that a controller would normally see out the windows of the tower cab without the need to move their head more than 220 degrees. Another Remote Tower benefit is that each aircraft within visual range can be tagged with that aircraft’s tail number, just as it might if the controller were looking at a radar screen. (more…)

-

Will 2018 Better Focus Our Aviation Future?

by

[sc name=”post_comments” ][/sc]

Happy New Year! I hope you all shared a safe and joyous celebration with family and friends. And warm. Let’s not forget warm. The air temp was double digits below zero here in Wisconsin, and the wind chill was about three times that. Avoiding hypothermia was, however, a good distraction from thinking about the inexorable march of time and our aviation future.

Happy New Year! I hope you all shared a safe and joyous celebration with family and friends. And warm. Let’s not forget warm. The air temp was double digits below zero here in Wisconsin, and the wind chill was about three times that. Avoiding hypothermia was, however, a good distraction from thinking about the inexorable march of time and our aviation future.A pragmatic realist, I know that for aviation, it could go either way. Whether it focuses on the positive or negative side of the line depends, in part, on your point of view of the past, present, and future. There is no better example of this than automation technology’s steady march into the cockpit. Aurora successfully demonstrated its autonomous UH-1H for the U.S. Marines at Quantico.

Passenger-carrying aircraft—airliners—are in technology’s sights, and it will, perhaps, forever solve the cyclic pilot shortages that plague commercial aviation. Again, whether this is good or bad depends on your point of view and aviation situation. General aviation’s future is more precarious. The outcome of several factors in 2018 will provide better focus on its future.

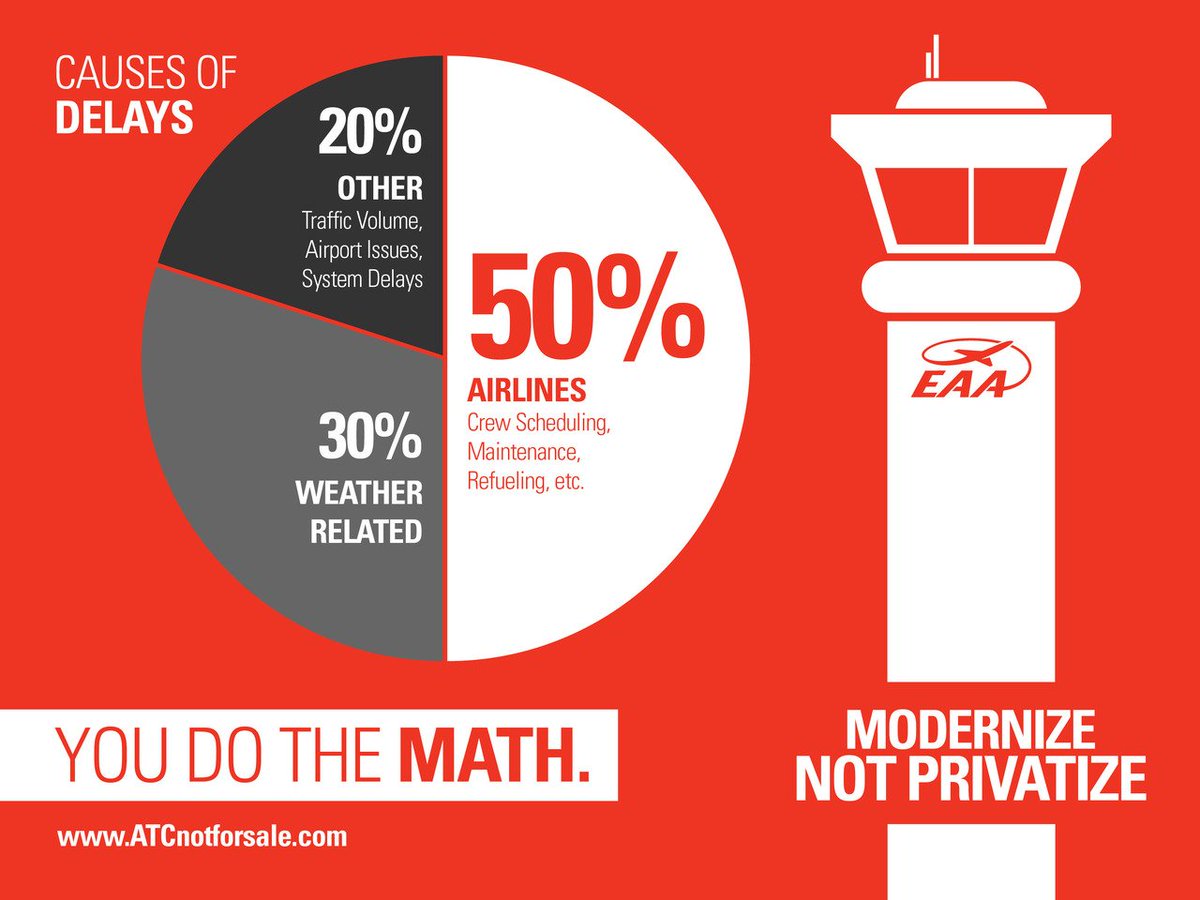

If the politicians give control of air traffic control to the airlines by privatizing the system, general aviation, as we’ve known it, it is a goner. This outcome will depend on how many people pull their heads out of vapid partisan ideological echo chambers and rise up as a concerted whole and firmly, but civilly, push the Star Trek mantra that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.

If the politicians give control of air traffic control to the airlines by privatizing the system, general aviation, as we’ve known it, it is a goner. This outcome will depend on how many people pull their heads out of vapid partisan ideological echo chambers and rise up as a concerted whole and firmly, but civilly, push the Star Trek mantra that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.This mantra could also be a greater salvation, because decades of income inequality affects more than those who can’t afford the dream of flight. In that regard, maybe giving ATC to the airlines would be a kinder end to general aviation, a coup de grace, as it were. Starvation, an insufficient number of new pilots and aircraft owners to sustain general aviation, is a more painful end.

How many aircraft owners decide this year to comply with the ADS-B mandate should bring this aspect of aviation’s future into better focus. The requirement for ADS-B capabilities takes effect two years from today. While the numbers vary, those who count them agree that the number of aircraft owners who installed the equipment is well off the pace that indicates full compliance.

This could mean that general aviation aircraft owners are either frugal procrastinators waiting for the best ADS-B deal or frugal Baby Boomers who will enjoy the freedom of flight until December 31, 2019, and then retire from the sky and sell their winged prides and joy. Two numbers will chart this course; those upgrading to ADS-B (and the volume of owners griping about the avionic shop lead time as they vie for precious openings) and the prices they ask when putting their aircraft up for sale (and the volume of their griping about the price relationship between supply and demand).

This could mean that general aviation aircraft owners are either frugal procrastinators waiting for the best ADS-B deal or frugal Baby Boomers who will enjoy the freedom of flight until December 31, 2019, and then retire from the sky and sell their winged prides and joy. Two numbers will chart this course; those upgrading to ADS-B (and the volume of owners griping about the avionic shop lead time as they vie for precious openings) and the prices they ask when putting their aircraft up for sale (and the volume of their griping about the price relationship between supply and demand).As it has since the Wrights launched the industry more than a century ago, only time will tell what course aviation’s future will take. But regardless of the outcome of its many challenges it has faced over its lifetime, and regardless of how the solutions to those challenges affected those involved, aviation continued in one form or another. And it will continue because it continues to covet fundamental contribution to humanity. — Scott Spangler, Editor

-

Price of Progress: Orville Wright’s Shower

by

[sc name=”post_comments” ][/sc]

It’s Kitty Hawk Day. Every December 17 I take a few moments to thank aviation for enriching my life and to appreciate the contributions and sacrifices of those, past and present, that made it possible. This reflection often involves an associated review of images, which led me to Orville Wright’s Shower, on the second floor of Hawthorn Hill, his home in Dayton. Better than anything else, it is a testament to the price he paid in furthering the art and science of flight.

It’s Kitty Hawk Day. Every December 17 I take a few moments to thank aviation for enriching my life and to appreciate the contributions and sacrifices of those, past and present, that made it possible. This reflection often involves an associated review of images, which led me to Orville Wright’s Shower, on the second floor of Hawthorn Hill, his home in Dayton. Better than anything else, it is a testament to the price he paid in furthering the art and science of flight.Hawthorn Hill, Wright’s Dayton home, was on the tour of sites that are encompassed by the https://www.aviationheritagearea.org/. Our guides were Wright’s great grand niece and nephew, Amanda Wright Lane and Stephen Wright, and Dr. Tom Crouch, senior curator at the National Air & Space Museum and Wright scholar, author of The Bishop’s Boys. He was the perfect person to ask about the large shower room on the second floor that resembled a half-hemispheric decontamination shower whose array of nozzles would leave no part of the body undrenched.

Referencing the crash at Fort Myer that took the life of Lt. Thomas Selfridge on September 17, 1908, Orville suffered a broken leg and ribs, as well as injuries to his back and pelvis, Dr. Crouch told me. For the rest of his life he suffered not only from everlasting pain of these injuries, but from greatly constrained physical range of motion. But being a Wright, he accommodated the price he’d paid in promoting aviation and the airplanes that made it possible, by designing this shower.

Referencing the crash at Fort Myer that took the life of Lt. Thomas Selfridge on September 17, 1908, Orville suffered a broken leg and ribs, as well as injuries to his back and pelvis, Dr. Crouch told me. For the rest of his life he suffered not only from everlasting pain of these injuries, but from greatly constrained physical range of motion. But being a Wright, he accommodated the price he’d paid in promoting aviation and the airplanes that made it possible, by designing this shower.Later that evening I returned to it and carefully stepped onto the tile floor and into the encircling silver array of nozzles. I wondered if Orville stood here, hoping the soothing spray of hot water would wash away the pain that was his constant companion. Did he think back to the cold and windswept dunes of Kitty Hawk when he and his brother launched their airborne journey and appreciate how luxurious a moment in this shower would have been then? It certainly crossed my mind as this train of thought led me to my participation in the hypothermic centennial celebration of that rain-drenched event.

Downstairs was a more personal accommodation of the price Orville paid to aviation. How many hours of reading there wore the knap off the upholstery of the chair he’d modified to hold a book on a swing arm? Probably many times the number he logged in flight. As he sat in that chair, did he look up from his book and remember the days, good and bad, that let up to it? What memories coursed through his mind on Kitty Hawk Day? Did he take a moment to quietly appreciate all that he’d accomplished, including the lessons learned from his failures? Did he, as I have, accept that for better or worse, it was all worth it, and then return his eyes and mind to pages before him. — Scott Spangler, Editor

Downstairs was a more personal accommodation of the price Orville paid to aviation. How many hours of reading there wore the knap off the upholstery of the chair he’d modified to hold a book on a swing arm? Probably many times the number he logged in flight. As he sat in that chair, did he look up from his book and remember the days, good and bad, that let up to it? What memories coursed through his mind on Kitty Hawk Day? Did he take a moment to quietly appreciate all that he’d accomplished, including the lessons learned from his failures? Did he, as I have, accept that for better or worse, it was all worth it, and then return his eyes and mind to pages before him. — Scott Spangler, Editor -

Insanity and the DOT Pilot Shortage Solution

by

[sc name=”post_comments” ][/sc]

As most sentient people know, insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Or maybe it is just laziness because developing a new, more efficient way of educating pilots is too much time, effort, and money. When it comes to evening out the pilot shortage cycles, it is much easier and economical to put a new name on a century of tradition unimpeded by progress.

As most sentient people know, insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Or maybe it is just laziness because developing a new, more efficient way of educating pilots is too much time, effort, and money. When it comes to evening out the pilot shortage cycles, it is much easier and economical to put a new name on a century of tradition unimpeded by progress.That’s what Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao did in announcing the department’s Forces to Flyer Initiative that will explore ways “to address this pilot shortage, and ensure our nation continues to be a world leader in aviation.” This three-year demonstration program has two objectives: to learn how interested veterans might be in becoming commercial pilots, and to help train those who are not already pilots.

That last part is where the insanity comes in. The program will provide financial support to veterans to earn their CFI. “As many of you know,” said Chao, “flight instructors can use their paid time to earn hours toward their airline transport pilot certificate.” Clearly, she doesn’t know or hasn’t talked to a flight instructor, ever. She probably thinks that the average flight instructor earns enough to keep a roof over their heads and food in their bellies by teaching alone, and that they are so busy that they’ll log the ticket-punching 1,500 hours in less than a year. Never mind that 1,500 hours in GA aircraft offers little preparation to fly an airliner of any size.

For those old enough to remember the GI Bill flight training benefits, see the definition of insanity. Such programs rarely last long enough for a good number of vets to complete training because politicians with short memories want to spend the flight training money on something more important to them and their campaign benefactors. For everyone else, consider the aviation tradition of “paying your dues” as a CFI and working your way up. It worked when aviation was in its infancy, but it no longer meets the needs of 21st century aerospace. But the people who own, operate, and invest in airlines like it because it saves them a lot of money that they skim off the bottom line as bonuses and dividends…until they don’t have enough trained people to drive their winged buses, but that only happens every decade or two.

For those old enough to remember the GI Bill flight training benefits, see the definition of insanity. Such programs rarely last long enough for a good number of vets to complete training because politicians with short memories want to spend the flight training money on something more important to them and their campaign benefactors. For everyone else, consider the aviation tradition of “paying your dues” as a CFI and working your way up. It worked when aviation was in its infancy, but it no longer meets the needs of 21st century aerospace. But the people who own, operate, and invest in airlines like it because it saves them a lot of money that they skim off the bottom line as bonuses and dividends…until they don’t have enough trained people to drive their winged buses, but that only happens every decade or two.If government rule makers were really interested in bringing pilot training and certification up to date, they should take a lesson from the performance based navigation system of requirements that is making flight from Point A to B more efficient. Performance based pilot certification would not be based on an arbitrary number of hours, like 1,500, but rather of each pilot’s demonstrated ability to meet the requirements of a particular type of flying in a particular type of aircraft.

Performance based pilot training sure seems to work for the military, which updates the performance parameters with the current and coming technology and equipment. And from their first flight pilots learn to fly so they can meet their ultimate performance requirements. Student naval aviators, for example, learn that pitch determines speed and power controls altitude, and flaring to land doesn’t work on an aircraft carrier. And as they meet the performance requirements at each stage of training, they will have logged about 200 hours, give or take, when they make their first trap.

This is a case where a tradition is the source of progress. but making this change in civilian flight training might just be too much to hope for because bottom-line interests of those who will support the education of the pilots they need are more important than progress. — Scott Spangler, Editor

This is a case where a tradition is the source of progress. but making this change in civilian flight training might just be too much to hope for because bottom-line interests of those who will support the education of the pilots they need are more important than progress. — Scott Spangler, Editor