-

Making the Brazilian ATR-72 Spin

by

[sc name=”post_comments” ][/sc]

Note: This story was corrected on August 10th at 10:23 am, thanks to the help of a sharp-eyed reader.

Making an ATR-72 Spin

I wasn’t in Brazil on Friday afternoon, but I saw the post on Twitter or X (or whatever you call it) showing a Brazil ATR-72, Voepass Airlines flight 2283, rotating in a spin as it plunged to the ground near Sao Paulo from its 17,000-foot cruising altitude. All 61 people aboard perished in the ensuing crash and fire. A timeline from FlightRadar 24 indicates that the fall only lasted about a minute, so the aircraft was clearly out of control. Industry research shows Loss of Control in Flight (LOCI) continues to be responsible for more fatalities worldwide than any other kind of aircraft accident.

The big question is why the crew lost control of this airplane. The ADS-B data from FlightRadar 24 does offer a couple of possible clues. The ATR’s speed declined during the descent rather than increased, which means the aircraft’s wing was probably stalled. The ATR’s airfoil had exceeded its critical angle of attack and lacked sufficient lift to remain airborne. Add to this the rotation observed, and the only answer is a spin.

Can a Large Airplane Spin?

The simple answer is yes. If you induce rotation to almost any aircraft while the wing is stalled, it can spin, even an aircraft as large as the ATR-72. By the way, the largest of the ATR models, the 600, weighs nearly 51,000 pounds.

Of course, investigators will ask why the ATR’s wing was stalled. It could have been related to a failed engine or ice on the wings or tailplane. (more…)

-

How the FAA Let Remote Tower Technology Slip Right Through Its Fingers

by

[sc name=”post_comments” ][/sc]

In June 2023, the FAA published a 167-page document outlining the agency’s desire to replace dozens of 40-year-old airport control towers with new environmentally friendly brick-and-mortar structures. These towers are, of course, where hundreds of air traffic controllers ply their trade … ensuring the aircraft within their local airspace are safely separated from each other during landing and takeoff.

The FAA’s report was part of President Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act enacted on November 15, 2021. That bill set aside a whopping $25 billion spread across five years to cover the cost of replacing those aging towers. The agency said it considered a number of alternatives about how to spend that $5 billion each year, rather than on brick and mortar buildings.

One alternative addressed only briefly before rejecting it was a relatively new concept called a Remote Tower, originally created by Saab in Europe in partnership with the Virginia-based VSATSLab Inc. The European technology giant has been successfully running Remote Towers in place of the traditional buildings in Europe for almost 10 years. One of Saab’s more well-known Remote Tower sites is at London City Airport. London also plans to create a virtual backup ATC facility at London Heathrow, the busiest airport in Europe.

A remote tower and its associated technology replace the traditional 60-70 foot glass domed control tower building you might see at your local airport, but it doesn’t eliminate any human air traffic controllers or their roles in keeping aircraft separated.

Max Trescott photo Inside a Remote Tower Operation

In place of a normal control tower building, the airport erects a small steel tower or even an 8-inch diameter pole perhaps 20-40 feet high, similar to a radio or cell phone tower. Dozens of high-definition cameras are attached to the new Remote Tower’s structure, each aimed at an arrival or departure path, as well as various ramps around the airport.

Using HD cameras, controllers can zoom in on any given point within the camera’s range, say an aircraft on final approach. The only way to accomplish that in a control tower today is if the controller picks up a pair of binoculars. The HD cameras also offer infrared capabilities to allow for better-than-human visuals, especially during bad weather or at night.

The next step in constructing a remote tower is locating the control room where the video feeds will terminate. Instead of the round glass room perched atop a standard control tower, imagine a semi-circular room located at ground level. Inside that room, the walls are lined with 14, 55-inch high-definition video screens hung next to each other with the wider portion of the screen running top to bottom.

After connecting the video feeds, the compression technology manages to consolidate 360 degrees of viewing area into a 220-degree spread across the video screens. That creates essentially the same view of the entire airport that a controller would normally see out the windows of the tower cab without the need to move their head more than 220 degrees. Another Remote Tower benefit is that each aircraft within visual range can be tagged with that aircraft’s tail number, just as it might if the controller were looking at a radar screen. (more…)

-

Aviation Safety Semantics

by

[sc name=”post_comments” ][/sc]

As a word merchant and an aviator, words are important. They are the foundation of communication, and in many instances they can be the difference between life and death. “Hold Short” is but one example. Equally important is our semantic understanding of the aviation lexicon, what each of the words mean.

As a word merchant and an aviator, words are important. They are the foundation of communication, and in many instances they can be the difference between life and death. “Hold Short” is but one example. Equally important is our semantic understanding of the aviation lexicon, what each of the words mean.Take “accident,” for example. Millions of words have been written and spoken about this word, its outcomes, its trends, and its persistent place in aviation. But have you ever given thought to what this word means? Here is what the 11th edition of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary has to say:

Accident—noun

1a: an unforeseen and unplanned event or circumstance

b: lack of intention or necessity : CHANCE

2a: an unfortunate event resulting especially from carelessness or ignorance

As this relates to aviation, accidents are unfortunate and, for the most part, unplanned. Suicidal best describes pilots who take off intending to return to earth unsafely. Pilots who consider aviation’s unfortunate outcomes unforeseen may best be described by the second aspect of the definition: careless and ignorant.

Pilots have been choosing from the same menu of fatal outcomes for more than a century now, so how can anyone categorize them as “unforeseen?” No one is ever immune from the possibility of any of them on any flight. Regardless of our intentions we each are ultimately responsible for the consequences of our decisions.

Every student pilot learns, to some degree or another, about Five Hazardous Attitudes, their symptoms, and the consequential umbrella that covers them all:

Anti-authority: Those who do not like anyone telling them what to do.

Impulsivity: Those who feel the need to do something, anything, immediately.

Invulnerability: Those who believe that accidents happen to others.

Macho: Those who are trying to prove that they are better than anyone else. “Watch this!

Resignation: Those who do not see themselves making a difference.

Knowing about these attitudes is good, but it is just a halfway effort without balancing them with some beneficial attitudes pilots should relentlessly strive to embody. You can compile your list, but here’s one to get you started:

Circumspect—adjective

: careful to consider all circumstances and possible consequences : PRUDENT

Employing all that this word embodies to every aspect of aviation before acting can only improve safety. But just as we each are responsible for the consequences of decisions whether they be good or bad, we humans are not infallible, so unwanted outcomes will continue to occur with unwanted regularity. But we should stop referring to them as “accidents.” The military has a better word and definition for it:

Mishap—noun

: any unplanned, unintended event or series of events that results in death, injury, illness, or property damage.

But whatever word you use to describe it, remember to be circumspect. — Scott Spangler, Editor

Did someone forward JetWhine to you? Subscribe Here and never miss another issue.

-

Do Electric Aircraft Face Lapse Rate Challenges?

by

[sc name=”post_comments” ][/sc]

Beyond worrying about the heating bill and bundling up for the sub-zero trek to the mail box, reports about how much of America has been dealing with the polar waterfall has stimulated an unexpected question: Given the reality that cold weather quickly sucks the electron life out of batteries, will electric aircraft face lapse-rate challenges?

Beyond worrying about the heating bill and bundling up for the sub-zero trek to the mail box, reports about how much of America has been dealing with the polar waterfall has stimulated an unexpected question: Given the reality that cold weather quickly sucks the electron life out of batteries, will electric aircraft face lapse-rate challenges?While watching a TV news report about desperate owners trying to revive their cold-sucked dead Teslas in Chicagoland, what immediately popped into my head was the reality that the ambient temperature in a standard atmosphere surrenders (lapses) approximately 3.5 °F or 2 °C per thousand feet up to 36,000 feet, which is approximately — 65 °F or — 55 °C. Above this point, the temperature is considered constant up to 80,000 feet.

That’s a lot higher than today’s prototype electric flyers now aviate, but I’m looking forward to their airline goals. But the temperatures at the airline’s cruising flight levels are a lot colder than it has been for the past week or so in much of the United States, roughly double our weeklong Wisconsin windchill. (This begs another question: Do batteries suffer from windchill, or is that just reserved for mammals? Google says it doesn’t.)

Installing battery warmers on these aircraft seems to be a logical solution, but they, too, would be electric, which would increase the draw on the storage system’s power reserves. And then there would be the added weight, the primary foe of power efficient flight. Battery temperature not only affects output, it has a negative effect on recharging the battery.

Electric vehicles, it turns out, have two batteries, one high-voltage and the other low, like the 12-volt battery that fires up an internal combustion powerplant. Apparently, like a vehicle that runs on dead dinosaurs, an electric vehicle with a cold-sucked 12 volt needs a jump to recharge its high-voltage counterpart more efficiently. Without the proper preparation, it seems, a recharge that takes an hour in milder temps can take four or five times longer when it’s cold. Not that airline turn-around crews need another time-suck challenge.

Electric vehicles, it turns out, have two batteries, one high-voltage and the other low, like the 12-volt battery that fires up an internal combustion powerplant. Apparently, like a vehicle that runs on dead dinosaurs, an electric vehicle with a cold-sucked 12 volt needs a jump to recharge its high-voltage counterpart more efficiently. Without the proper preparation, it seems, a recharge that takes an hour in milder temps can take four or five times longer when it’s cold. Not that airline turn-around crews need another time-suck challenge.The Cold Weather Best Practices in the Tesla Model 3 Owner’s Manual was eye opening. Just as ice and snow on an airframe is detrimental to flight, on an electric car, its “moving parts, such as the door handles, windows, mirrors, and wipers can freeze in place.” This includes the charging port. “In extremely cold weather or icy conditions, it is possible that your charge port latch may freeze in place. Some vehicles are equipped with a charge port inlet heater that turns on when you turn on the rear defrost in cold weather conditions. You can also thaw ice on the charge port latch by enabling Defrost Car on the mobile app.”

This assumes the vehicle still has some battery power left, not to mention the phone needed to run all the vehicle’s apps. I’m sure the electrical aviation engineers are working on all these challenges, and all the others I’m unaware of. I wish them well. The sun has warmed the outside temperature to a positive single digit, and the mail truck just delivered, so it’s time to bundle up. — Scott Spangler, Editor

-

Making Like Maverick in an L-39

by

[sc name=”post_comments” ][/sc]

By Rob Mark

An early scene in An Officer and a Gentleman, the 1982 movie about U.S. Navy recruits slogging their way through officer candidate school, has granite-tough Marine Gunnery Sgt. Foley (actor Lou Gossett Jr.) confronting candidate Zack Mayo (actor Richard Gere) nose to nose.

“Now why would a slick little hustler like you sign up for the Navy?” asks Foley.

Mayo’s response grabbed me. “Because I want to fly jets, sir!”

I’ve been flying jets for years as a corporate pilot, but not real jets to some … like fighter jets. When opportunity knocked with an offer to fly an Aero Vodochody L— 39 Albatros (one “s” in the Czech spelling)—a single-engine bird still used as a basic trainer for some nation’s fighter pilots—I jumped at the chance. And I seldom thought much about Top Gun either (“Do some of that pilot stuff, Maverick”) before my first day of training at Gauntlet Warbirds, based at Aurora Municipal Airport (KARR) west of Chicago. In a nice-job-if-you-can-get-it situation, Greg Morris serves as Gauntlet’s owner and chief pilot (see “Pilots: Greg Morris,” December 2011 AOPA Pilot).

The panel on the L— 39 is a conglomeration of normal gauges, except some, are labeled in English, and others still in Cyrillic.

The panel on the L— 39 is a conglomeration of normal gauges, except some, are labeled in English, and others still in Cyrillic.My goal in these Gauntlet jet-training sessions? Cram enough L— 39 knowledge and skill into my brain to pass a type-rating checkride. With very little onboard deice equipment, the L— 39 is, however, a VFR-only bird. In a non-U.S.-certified Experimental aircraft like the L— 39, the end result is called an Experimental Aircraft Authorization. Morris explained that the Experimental moniker also prevents Gauntlet from charging for rides. A pilot with any kind of certificate can begin training right away in the familiarization course where dual instruction is $2,200 per hour. Only if a pilot chooses the complete course with a checkride is an instrument rating required. The total cost will vary according to the student’s experience level and can run from six to 20 hours. And almost before I could ask, Morris said, “The FAA allows P— 51 rides, though, under a special exemption. If they’d grant us an exception, I’d need another L— 39 immediately to handle the business.”

The Walk Around

Morris and I began with a walk around N992RT, a 1974 C-model Albatros. Other versions ready the L— 39 for light-attack missions. On first glance at its near-stiletto nose, it’s clear the 10,300-pound Albatros is fast. Down low, maximum speeds can easily exceed 425 knots. However, this airplane is also designed with systems simple enough—and handling qualities docile enough—to allow no-jet-time aviators to confidently solo in as little as 15 hours. But good jet flying is still demanding. Morris says that his no-previous-jet-time customers usually need between 15 and 20 hours to complete the training. “You’d think pilot problems would be all about stick-and-rudder skills here,” he said. “But most of the time, problems pop up because students simply haven’t spent enough time with the books. They need to know the L— 39’s systems and our profiles cold when they walk in the door.” Not much different than corporate flying.

Preflight means ensuring the controls move properly, the pitot probes are undamaged, the oil level is sufficient, and both engine intakes—so dark you always need a flashlight—are clear of debris. You scramble up the side of the Albatros before you climb in, where the L— 39 seat is not comfortable, not even a little bit. But then, you’re sitting on a parachute and a disarmed ejection seat. I eventually did find some degree of comfort, even with that big, fat, five-point harness; a helmet; visor; and an oxygen mask.

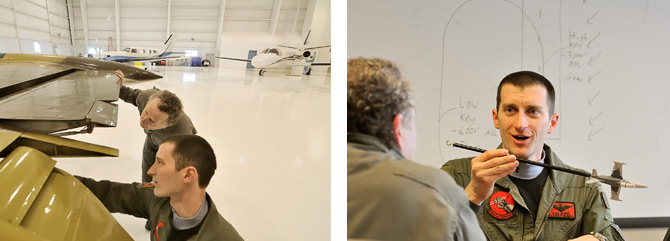

The author and Greg Morris review the aircraft flight envelope during ground school (right). The L— 39’s Fowler flaps are clearly visible during the preflight inside Gauntlet Warbird’s hangar at Aurora Municipal Airport (left).

Many of the panel gauge identifications are written in Cyrillic, with metric scales, the panel looks much like that of a U.S.-built fighter jet—including the narrow and mildly pressurized (4 psi) cockpit. The big throttle on the left side includes a thumb-operated speed-brake switch to make extension and retraction of the boards beneath the belly easy. The checkout includes a brief on the L— 39’s castering nose gear. Steering happens through coordinated use of brakeless rudder pedals augmented by a handbrake, which looks like it was swiped from a 10-speed bike, attached to the control stick. Need a right turn? Hold full right rudder and gently grab the handbrake. “That braking system is the single thing that gets everyone,” Morris told me. “I constantly get thrown around in the backseat while we’re on the ground as folks get used to it.” He joked, “That’s one reason I wear the helmet.”

The 3,800-pound-thrust Ukrainian-built AI25-TL engine needs an air-assisted start provided by the onboard Sapphire APU. Once it spins up the engine we begin taxi practice to the runway, something a bit akin to learning to steer my old taildragger. Like most jets, before-takeoff items are few, except for the slam check, where I shove the throttle from idle to full power to time how long it takes to reach full power, normally about 12 to 14 seconds, which is why you almost never, ever pull the throttle back to idle if you’re high or fast on final, for example, where speed brakes would be adding drag as well.

A Bit Like a Taildragger

I still zig and zag a bit with those brakes for the lineup and hold them while I run the engine to full power—106 percent—before releasing the brake handle. Steering is quite easy as we shoot down the runway. At 90 knots I ease the stick back and we’re through 140 knots with gear and flaps coming up before I know it. In a 200-knot climb, we’re rocketing at 3,000 fpm toward the VFR Gauntlet practice area west of Aurora Airport.

Morris was right. The L— 39 is a breeze to fly—light and responsive on the controls. My 200-knot steep turns begin at 14,500 feet with gentle banks. Morris asks to show me a few. He effortlessly cranks that puppy into 45- to 50-degree banks. I try and now it’s really fun, even though the L— 39 is clearly sensitive in pitch. “You really need to include the attitude indicator in your scan,” he tells me. “Even a small angular change from the horizon quickly translates into a huge velocity change.” I’ll need to work on these.

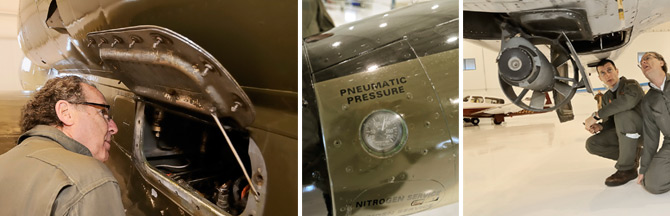

Preflight demands a check of the ram air turbine (right), pneumatic pressure (middle), and a look inside the variety of other access panels (left).

Next comes a roll looking out the huge glass canopy. Now I’m really loving this airplane. The stalls are very simple—wait for the buffet and recover. But a secondary stall awaits any pilot who recovers with too much back pressure, too quickly.

The traffic pattern is where the fun really begins as we try out the Albatros as a touch-and-go birds. I was almost exhausted after the first hour-long pattern session before I realized that bizjet pilots don’t normally fly VFR touch and go; approaches and go-arounds, yes, but not touch and goes. Because the Albatros can accelerate so quickly, Morris tells me to fly the upwind and prepare for a quick 180-degree turn back to downwind all at once, pulling the power back just before we reach pattern altitude.

Let the Nose Fall??

In the pattern, you can’t let the speed get away from you or the patterns become ugly, as Morris mentioned in the briefing. It sounded easy, but on the first few, I found myself with the power back, nose up high, and in a turn wondering what might be coming next. “Don’t try to hold everything up,” Morris instructs. “Just let the nose fall as you turn. If you don’t reduce the power quickly as you unload the nose, you’ll easily gain 70 knots turning downwind.” After a few tries, my turns plunk me right on downwind at just under 200 knots. “That’s perfect,” Morris announces. I began to breathe a bit as each landing started to improve on the last.

Reminding me of that slow engine spool-up time, Morris said we’d fly base at 140 knots with the speed brakes extended, demanding high power settings that prepare the engine for instant response in the event of a go-around. On short final, I slow to 120 knots and hold it off like a Cirrus. Some were even more fun as I held the nose up high for a little aerodynamic braking, just like those F— 16s I always watch at AirVenture. On a touch and go, as soon as the nosewheel was down, I slammed the throttle in because of that spool-up time again. By the time I return the flaps to takeoff, we’ve reached 90, and the power’s back at max.

Reminding me of that slow engine spool-up time, Morris said we’d fly base at 140 knots with the speed brakes extended, demanding high power settings that prepare the engine for instant response in the event of a go-around. On short final, I slow to 120 knots and hold it off like a Cirrus. Some were even more fun as I held the nose up high for a little aerodynamic braking, just like those F— 16s I always watch at AirVenture. On a touch and go, as soon as the nosewheel was down, I slammed the throttle in because of that spool-up time again. By the time I return the flaps to takeoff, we’ve reached 90, and the power’s back at max.In L— 39s, the last maneuver to learn is a Simulated Flame Out (SFO) approach, essentially like the instructor pulling back the throttle of a 172 to watch the pilot’s reaction. Since engine failures in fighters are likely to happen up high, simply looking out the window for a great field seldom works. A successful maneuver becomes all about energy management, so pilots don’t end up too high or too fast at the wrong time. Now the blackboard drawings Morris made illustrating Gauntlet’s SFO procedures made more sense. “Some people try to make up their own procedures when they’re nervous,” Morris told me. “When they eventually start flying the way we teach them, it usually all falls into place.”

The SFO practice actually begins near the airport at roughly 3,000 feet agl. Turn final two miles out at 200 knots and cross the numbers headed upwind, a point called High Key. Students set the throttle at 70 percent N1 and try to not touch it again until just before the touchdown. The pilot now blends only the use of flaps, gear, and speed brakes together with a pitch to make the runway. At the numbers, the pilot begins a single 180-degree turn back to downwind. At the Low Key point, opposite the numbers, it becomes easier to figure out whether the plan will work. Morris says a good instructor can see a successful SFO coming a half-mile away. I’m still working on mine.

And so the training hours passed and I eventually began to feel more comfortable in this tiny fighter-plane cockpit—now that I was accustomed to the myriad foreign-language dials and gauges, that is. In the end, the L— 39—as slick as I thought it was during that first round of touch and goes—flies just like an airplane, a quite good one, of course, thinking back to a roll rate that could easily knock my eyeballs from side to side if I wasn’t careful. When I look back at checking out in a Cirrus SR22, I thought that, too, was quite an eye-opening experience at the time. Now that I was preparing for the check ride, I realized the L— 39 too would someday become just another airplane in the list of those I’ve flown. Yeah, right, Maverick!

Robert Mark publishes Jetwhine.com. This story was reprinted here with permission of AOPA Pilot where it ran originally.