Theodor Knacke & Parachute Appreciation

When looking at the details involved, designing a decelerator system is one of aviation’s premier engineering challenges. Working with a variety of sewn together textiles an engineer must create an aerodynamic system that reliably assembles itself in midair. Sounds simple, doesn’t it? Let’s consider the parachute used in an F-18. It must fully deploy so an aviator does not come to a sudden stop after ejecting at zero speed and zero altitude. At the other end of its performance spectrum, the parachute must assemble itself in such a sequence that it does not self-destruct when it unfolds at 40,000 feet in a Mach number slipstream. And just to make it interesting, the parachute must be packed and hydraulically mashed into a solid textile brick that is wedged into the top of a seat under a canopy where the brick bakes on sunny days, freezes at altitude, is bathed it corrosive salt sea air for months and months and months.

When looking at the details involved, designing a decelerator system is one of aviation’s premier engineering challenges. Working with a variety of sewn together textiles an engineer must create an aerodynamic system that reliably assembles itself in midair. Sounds simple, doesn’t it? Let’s consider the parachute used in an F-18. It must fully deploy so an aviator does not come to a sudden stop after ejecting at zero speed and zero altitude. At the other end of its performance spectrum, the parachute must assemble itself in such a sequence that it does not self-destruct when it unfolds at 40,000 feet in a Mach number slipstream. And just to make it interesting, the parachute must be packed and hydraulically mashed into a solid textile brick that is wedged into the top of a seat under a canopy where the brick bakes on sunny days, freezes at altitude, is bathed it corrosive salt sea air for months and months and months.

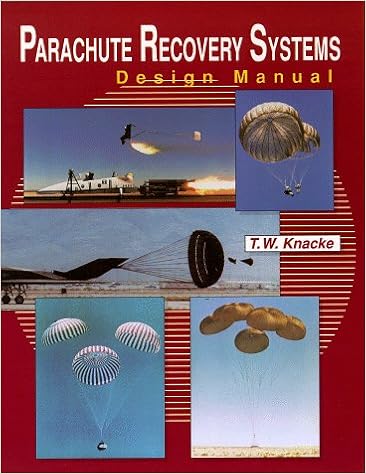

And the engineer who wrote the book—literally—on meeting this daunting engineering challenge? Theodor Wilhelm Knacke. Don’t bother looking him up on Wikipedia. He doesn’t exist there. But he should, because among his many accomplishments is his compilation of all he’d learned about the field in Parachute Recovery Systems Design Manual. The photos on its cover depict some of the projects on which he worked. That effort began in 1930s at Flugtechnisches Institute Stuttgart (or Flight Institute of Stuttgart Technical University, FIST), which challenged him and a colleague, Georg Madelung “to develop a parachute suitable for the in-flight and landing deceleration of aircraft.” Their solution was the ribbon parachute, which led to the ring slot and ring sail parachutes that made “31 successful earth landings” of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo spacecraft.

And the engineer who wrote the book—literally—on meeting this daunting engineering challenge? Theodor Wilhelm Knacke. Don’t bother looking him up on Wikipedia. He doesn’t exist there. But he should, because among his many accomplishments is his compilation of all he’d learned about the field in Parachute Recovery Systems Design Manual. The photos on its cover depict some of the projects on which he worked. That effort began in 1930s at Flugtechnisches Institute Stuttgart (or Flight Institute of Stuttgart Technical University, FIST), which challenged him and a colleague, Georg Madelung “to develop a parachute suitable for the in-flight and landing deceleration of aircraft.” Their solution was the ribbon parachute, which led to the ring slot and ring sail parachutes that made “31 successful earth landings” of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo spacecraft.

Sources are divided on when Knacke immigrated to the United States, but in the end it really doesn’t matter if it was 1946 or 1947. More important is that Operation Paperclip recruited him after World War II. This, too, was a surprise. Operation Paperclip is most famously associated with snatching Werner von Braun and his team of rocket scientists before the Soviets could get to them, but the program ran from 1945 to 1959 and recruited more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians.

In the United States Knacke went to work for the U.S. Air Force, as a research engineer at Wright Field’s Parachute Branch and then, from 1952 to 1957, as technical director of the 6511th Test Group (Parachutes) at El Centro, California. His first assignments were to fit the B-47 and then the B-52 with drag chutes, and to improve the ribbon parachute. Hired as the vice president of engineering at Space Recovery Systems in 1957, in 1962 he became the chief of technical staff for recovery systems for the Ventura Division of the Northrup Corporation, responsible for all areas of missile, drone, and spacecraft recovery.

In the United States Knacke went to work for the U.S. Air Force, as a research engineer at Wright Field’s Parachute Branch and then, from 1952 to 1957, as technical director of the 6511th Test Group (Parachutes) at El Centro, California. His first assignments were to fit the B-47 and then the B-52 with drag chutes, and to improve the ribbon parachute. Hired as the vice president of engineering at Space Recovery Systems in 1957, in 1962 he became the chief of technical staff for recovery systems for the Ventura Division of the Northrup Corporation, responsible for all areas of missile, drone, and spacecraft recovery.

Knacke retired from Northrup in 1977 and pursued an active consulting career for the U.S. Army, Navy, NASA, and industry. A fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, AIAA not only presented him with its Aerodynamic Decelerator Systems Award in 1981, which is bestowed every other year, they named it for him. Born on December 10, 1910 in Zitlow, Germany, Theodor Wilhelm Knacke died on January 18, 2001 at age 90. But his contributions continue not only through his design manual and scores of patents and papers, but through the parachute engineers he mentored and through the the interactive exchange of knowledge at his lectures and AIAA workshops. Perhaps one of them will one day author a Wikipedia page to share Knacke’s contributions to a larger audience and ensure his immortality. — Scott Spangler, Editor